Kevin Lincoln

The Moon Reflected

17 Feb - 12 March, 2022

This suite of paintings of the moon over water is a response to the artist’s meditations on nocturnal states of being. Traditionally, the night has stood as an emblem of Melancholy, and while an air of melancholy is not entirely absent from these works, the moon’s presence here is one of hope and an antidote to sorrow. And it is part of the mysterious power of these paintings – and perhaps their meaning, that the moon itself is not depicted ... for what do reflections conjure if not thought?

Neither anecdotal nor romantic, the particular poetry of this suite of paintings, made in the last months of 2018 into early 2019, provokes reverie and recognition of some universal experience of the night and her companion moon. The works seem to be imbued with the spirit of Japanese poems known as tanka. The abbreviated and strict prosody of that sustained and revered Japanese art form, chimes with the pervasive mood of Lincoln’s art. Consider this tersely elegiac verse:

The troubled waters

Are frozen fast,

Under clear heaven

Moonlight and shadow

Ebb and flow

This poem, written in eleventh-century Japan, is as resonant today as it must have been then. (Its author, Murasaki, is famed for the Tale of Genjii. ) As one of the poem’s many translators notes, “Japanese poetry does what poetry does everywhere: it intensifies and exalts experience.” And so it is with these paintings. Their tenebrous world holds a mirror to both the night-time of our waking and our dreaming and to the places we tread.

“Moonlight and shadow / ebb and flow”: these words – and their coupling – perfectly describe Lincoln’s central motifs and the mood they convey. But so too does the stripped, succinct brevity and formal constraint of the poem’s shape and weight; both Lincoln’s paintings and Murasaki’s poem embody experience and thought with strictly pared back means.

Lincoln has long been known for his embrace of and affinity with certain aspects of Japanese art and sensibility, and Murasaki’s succinctly evocative verse is but one instance of this synergy. Across the lower edge of one of the paintings (titled “The Way”), Lincoln has loosely inscribed the last line of a poem reproduced as one of the famed couplings of Japanese poems by Hokusai with his woodblock prints, drawn from the publication Hokusai, One Hundred Poets, a copy of which Lincoln owns.

The poem by Minamoto no Muneyuki reads,

Winter loneliness

In a mountain hamlet grows

Only deeper, when

Guests are gone, and leaves and grass

Withered are; - so runs my thought.

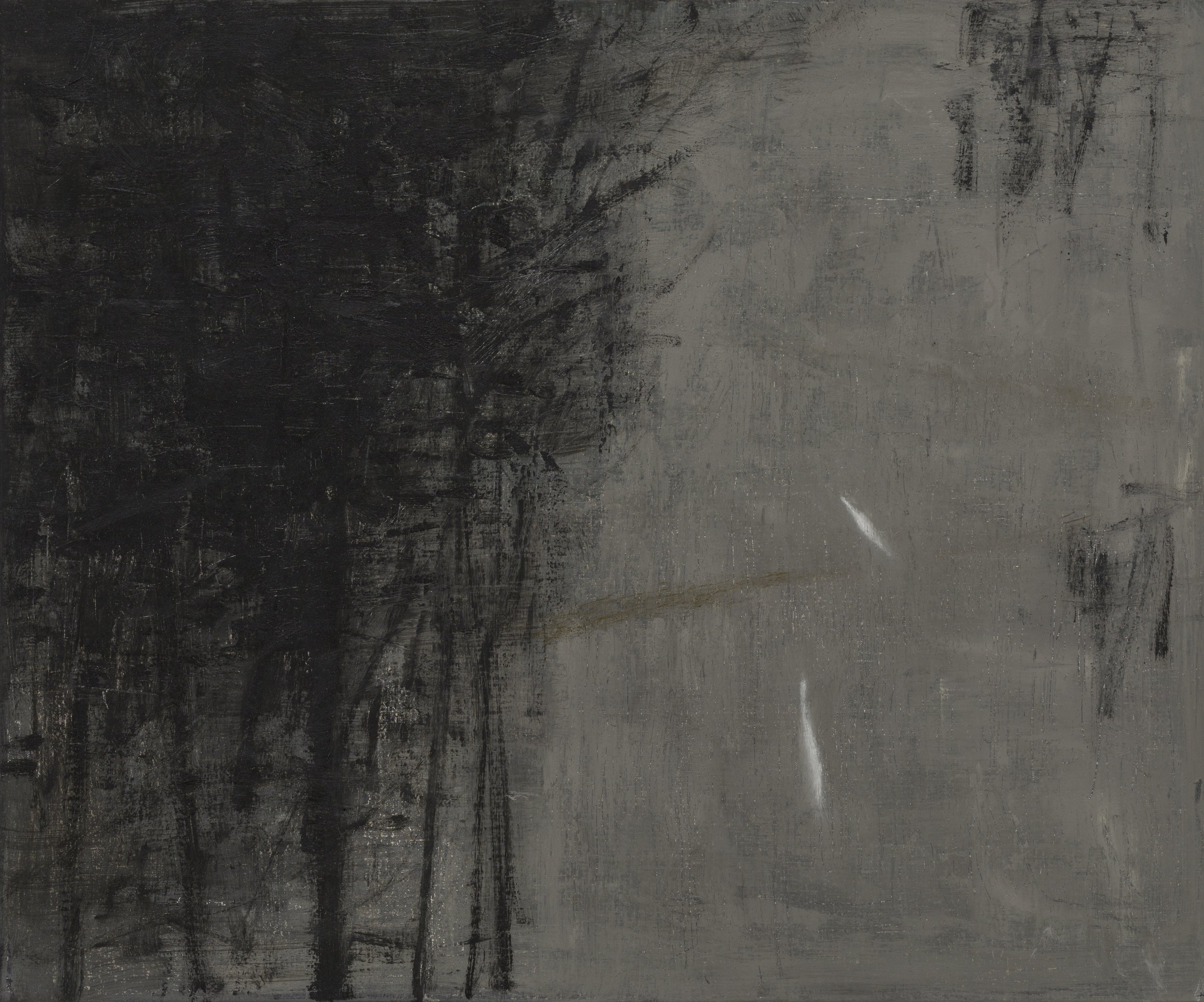

While Kevin Lincoln is clear that this suite of paintings arose from no place he can name, in both this and so many of these exalted ancient tanka poems there is something haunting and solitary which illuminates and parallels much that characterizes Lincoln’s intensely felt and coherently realized body of work. The two paintings titled “The Moon on Water” (I and II) - from late 2019 and 2020 respectively – both luscious, painterly canvases, almost square in shape – are almost abstract in their gestural markings. In the first of these vertical, trailing lines, almost black, animate the surface of what we read as water in a way that evokes reeds or perhaps the posts of an oyster bed. In the later canvas, these swiftly drawn lines are much closer to us, tracing the passage of, say, a sea bird diving for fish; while the stuttering inky black paint across the upper register of the canvas establishes the density of a riverbank. We are never in doubt that we are in the presence of water, nor that we are engulfed in the still, velvety night where “Moonlight and shadow / ebb and flow” hold sway.

In the magically silvery little painting “The Moon Reflected, IV”, the water across whose surface the moon traces what in Scandinavian countries is described as a pathway to the heavens, might well be frozen. The light shimmering on the water’s surface here echoes the “frozen fastness” of Murasaki’s poem.

Or take these lines written by the Emperor Uda, who reigned from 880 to 897,

Like a wave crest

Escaped and Frozen,

One white egret

Guards the harbour mouth

Substitute the word ‘crane’ for ‘egret’, and it is as though these words may have been written with Lincoln’s “Crane and Moon” in mind.

The three diptychs whose eponymous titles give this exhibition its name depict the resonant duality of light and darkness that lies at the heart of this suite of paintings. The “Moon Reflected” title conjures a nuanced play with both form and meaning. These diptychs render these opposites explicit; and while dark and light are paired, as though inseparable, perhaps this coupling serves to acknowledge that from the dark, light will come.

Lincoln’s tenebrous authority grows in the two long polyptychs, “Moonlight and Water” and “The River” where his quiet play with enveloping darkness and oblique illumination across their many panels is reminiscent of the movements comprising a piece of music - where changes of key, tonality and thematic repletion orchestrate the mood of music’s expressive register.

Lincoln’s paintings are also at once reductively, elegantly simple in a formal sense and yet mysteriously complex in their evocative emotional power and presence. Taken as a whole, we are in the presence of a repertoire of mood and emotion both compelling and symphonic. While we can clearly see how the brushstrokes comprise the elements of each painting, yet we are visually transported beyond this evidence of making. The visible brush marks in each of these paintings act as signs to something they are not, as we are held by the emotional resonance they provoke in us.

Altogether, these paintings seem simultaneously cosmic and particular: they exist between night and day, between dream and waking, between reality and imagination, between observation and invention. These are the spaces in which Kevin Lincoln’s works reside, the places from which his art is fashioned. Those who know this artist’s work will already recognise this. Those who have yet to discover his quiet authority and meditative art have a deeply rewarding journey before them.

Elizabeth Cross,

December 2021